A Day in the Borderlands by Karen Bell

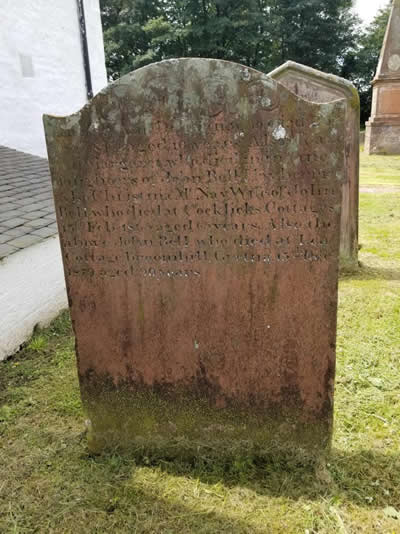

I have been interested in history and literature ever since I was kid. I attribute this to my fourth- grade teacher, Mrs. Graham, who made Ohio history as interesting as any story in the books I liked to read. Because of Mrs. Graham, I urged my parents to drive me around to cemeteries on weekends to collect information from the gravestones. It wasn’t hard to convince my parents. They liked history too, knew quite a bit about their ancestors, and they could take our dogs right along with us. Later while an English major at The Ohio State University, I discovered that the Bells were mentioned in The Childs Ballads: English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Who wouldn’t be intrigued by the Ballad of Adam Bell, Clym of the Clough, and William of Cloudesley? In the tradition of Robin Hood, these gentlemen were famous outlaws of the Scottish/English border. The ballad tells of Clym being captured by the English and taken to the castle in Carlisle, England, where he was imprisoned until Adam Bell rode in on his horse and rescued him. I wanted to know more about my outlaw ancestors, known as the Border Reivers. I don’t know if Adam was related to me, but I was successful in tracing my own ancestors back to the same area around Dumfries, Scotland and the English border. My research indicated that my ancestors had left Dumfries in the middle 1600s, lived for a generation or two in Northern Ireland, and arrived in Pennsylvania in the late 1600s or very early I was delighted when I found a cousin on Ancestry.com who was living in Belfast, Northern Ireland. I contacted him. Stephen Love is his name, and we struck up a lively friendship. The next thing I knew, he had invited to visit him in Belfast in May, 2018. We had such a good time that I returned again in July 2019 with my daughter, Tess. We had planned a trip to Edinburgh which had resulted in Stephen’s brother, Barry, renting a cottage in Hawick, Scotland. Barry suggested we dip down into England to see Hadrian’s Wall and visit the castle at Carlisle on the way. I was beyond thrilled to be going to England. But to get there, we had to drive through Dumfries. I had never wanted to ask them to take me to Dumfries because it’s not on the usual tourist site lists, and I didn’t want to impose on them in the same way I’d done on my parents all those many years ago. However, I thought that since we were already there, I would ask if we could stop in some cemeteries on our way and look for the graves of Bells. I was really excited about the prospect. Tess had an agenda of her own. She too had also been an English major at The Ohio State University. When she found out that we were going to be in Dumfries, she announced that she had always wanted to go there too but for a different reason. While taking a Medieval lit class, she had read The Dream of the Rood, a famous Old English poem. She had learned that a fragment of the poem was carved on the Ruthwell Cross that was located somewhere in Dumfries. Barry, amiable as always to adventure, googled the cross and discovered that it was on the way to Hadrian’s Wall. We decided that rather than search for Bells in cemeteries along the way, we would go directly to Ruthwell Village and see the cross. I was a little disappointed but decided to make the most of it. After all, I was in Dumfries. After a long and twisting ride through back roads, tiny villages and grazing lands of southwestern Scotland, we finally arrived at Ruthwell Village. What a surprise when we walked through the church yard gate, and Stephen nearly tripped over a gravestone inscribed with the name Bell. Looking around we found that many other Bells were buried there in the early 1800s. They weren’t my ancestors because my ancestors were already in Pennsylvania by then, but we all probably shared the same ancestors at some time in the past.

My daughter, Tess, saying, “I told you so” upon discovering the wealth of deceased Bells found in the grave yard.

Tess, had a bit more difficulty finding her treasure than I had finding mine though. The church door wouldn’t open. She could tell that it was not locked because she could feel the knob turn freely. It was stuck so she pushed a little harder and it opened, having been blocked by the floor mat inside. It was a truly thrilling moment when the door finally opened enough for us to squeeze through. We saw the cross immediately. It was ancient.

The Ruthwell Cross was carved in the 8th Century and is one of the most important monuments to survive from the Anglo-Saxon period. This stone cross stands at over 30 feet high. It’s ornately carved in the runic alphabet and with inscriptions in Latin and in Old English (the language of the Anglo-Saxons) and various scenes from the life of Christ. It is important in the study of English literature because of an inscription in runes of a version of The Dream of the Rood which is one of the oldest surviving poems written in Old English. The poem tells the story of the crucifixion of Christ from the perspective of the tree that was cut down to make the cross. The only other known surviving copy of the poem is housed in Vercelli Cathedral’s Chapter Library in northern Italy. During the time of the Reformation the Ruthwell Cross was taken down and partially buried here in Ruthwell. It was reconstructed in the 19th century, and a special nave was built in the church

We had a lovely encounter with this curious crew at the farm next to the church. They ran to the stone wall to observe us more closely.

My cousins think it’s amusing that I make them stop along the roads every so often so I can engage with a herd of grazing sheep, goats or cows. Stephen claims to be “afraid” of cows, making comments like, “The big feckers should not be allowed to roam freely.” I have always suspected he exaggerates this fear because he knows he makes me laugh. I think I was proven correct when this lovely girl stuck her nose over the wall to look at us and possibly receive a scratch on the nose, and he immediately began talking to her in the soft tones and high voice he reserves for his terrier, wee Oscar. “Oh, Hello, dear. Aren’t you a pretty cow?”

As we drove out of the Ruthwell Church, I looked up just in time to see this sign on the adjacent dairy farm where the curious cows lived. We had spent so much time at Ruthwell that I was afraid we wouldn't have time to do all we'd planned, but Barry, known for exceeding the speed limit, had no problem keeping us on schedule to Hadrian's Wall and Carlisle. Indeed, he drove so fast that I accused him of cutting the "d" off the end of England. In other words, he can drive by a sign faster than I can snap a picture on my

This is Hadrian's Wall. I was standing on the English side.

An English tree.

Stephen at Hadrian’s Wall. I think the wall was more of a psychological barrier than a physical one even though people were shorter back then.

Stephen's favorite sign

Wee Oscar

Castle.

Remnants of the castle moat.

Carlisle Castle is formidable enough even today although Barry seems undaunted, perhaps like Adam Bell.

The Castle Gate.

I imagined Adam Bell riding through the gate, barely escaping its wicked teeth, to rescue his friend, Clim of the Cough.

I wish I could thank my fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Graham, for setting me on this adventure so many years ago. I think she would be proud of me. If she only knew what a truly great teacher she was.

|